Let’s face it: Neal Spelce is both a legendary media professional and a witness to presidential history. Due to spending part of his career with President Lyndon Baines Johnson, his life course changed as he shares in his new book, With The Bark Off, A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media. This exclusive excerpt is chock full of his recollections of the Johnson family, as well as Spelce’s point of view on today’s media landscape. Here, our Lance Avery Morgan continues his conversation with Spelce about his book, and to learn more about his point of view and why Texans have always played a large role in the shaping of our culture.

All photography courtesy of Neal Spelce

The Curated Texan conversation continues with Neal Spelce, author of With The Bark Off, in this exclusive interview…

Lance Avery Morgan: Neal, With The Bark Off is the name of your book. Can you share the background on the title and why you chose it?

Neal Spelce: With The Bark Off is a phrase that I first heard inside the LBJ library, used by Lyndon Johnson. It was when he was talking about what was going to be in his presidential library that was then just getting ready to open. The grand opening had so many important people in attendance, including presidents, in the audience. I thought was such a neat phrase. He was saying that in the library, everything is there. In other words, nothing was hidden…it’s all there. He said that it’s not going to just show the joys and triumphs, but also the sorrows. So, when I started writing this memoir, it was straightforward. It’s all true. Everything that I write is…with the bark off.

The very first time I heard that phrase, LBJ walked up to me just before the ceremony when the library opened. He said as I followed him to the bathroom where LBJ sometimes held quick conversations, “Neal, I want you to listen to my speech.” I said, ‘All right, sir, be glad to.’ He started reading his speech on three-by-five cards and what he said about the library was true…it was with the bark off.

LAM: You two never missed a beat with each other, it seems. LBJ is a big part of your book, and he was a big part of your life. Tell me about that if you don’t mind, Neal.

NS: We’re kind of re-living it through this memoir, but I first saw LBJ when I was a 12-year-old barefoot kid in Raymondville, Texas in 1948. I heard this helicopter outside and a voice come over on loudspeaker saying, “Come on down to the softball field, we’re gonna have a little rally.” It turns out it was LBJ campaigning in 1948 for the U.S. Senate. My brother and I stood there, fascinated by a helicopter, which we had never seen before.

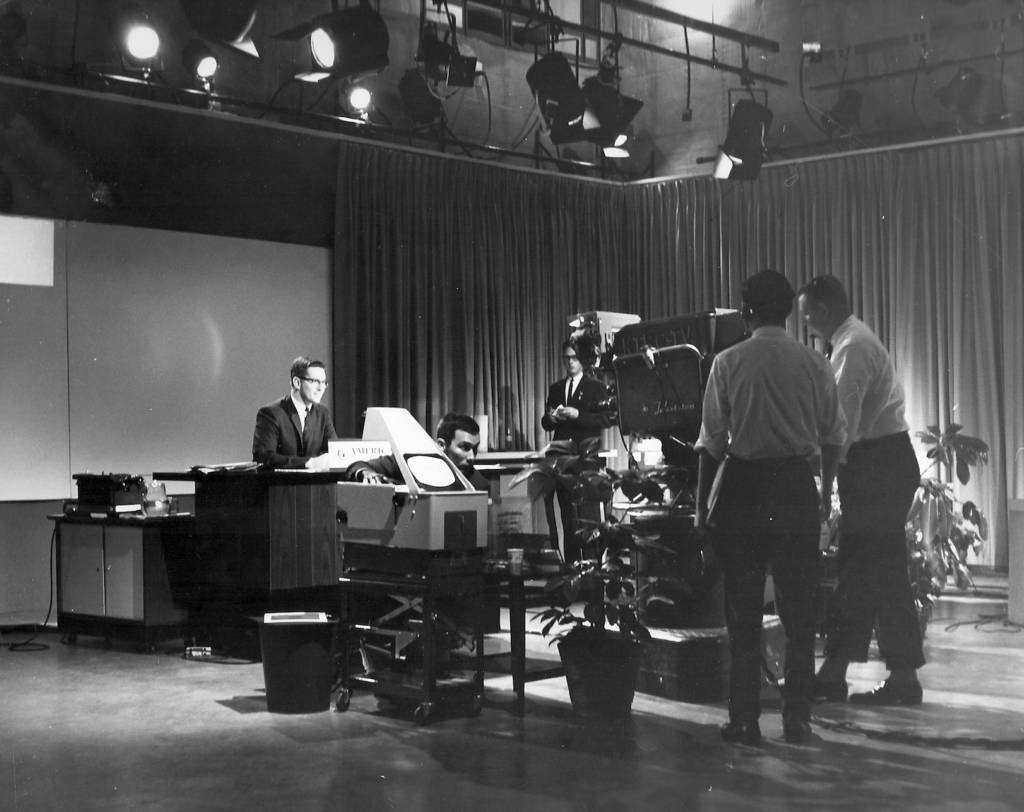

Fast forward to when I got to the University of Texas, I had a fantastic professor named DeWitt Reddick, who knew I was interested in broadcasting, journalism, and television. This was in 1956 and he told me that Bill Moyers, who was working at KTBC TV in Austin, was getting ready to leave. “Do you want me to recommend you?” he asked. I said, “Oh, hell yes.” So, I was hired at KTBC, which was owned by the Lyndon Johnson family. The first time I met LBJ face to face was after I started working there on a part-time basis as a news writer. Paul Bolton, the news director, said, “Do you want to meet the Senator?” LBJ was the Senate majority leader at the time, and I was in awe. I don’t remember much about the initial meeting, except that he told me, “Neal, I just want you to know that whenever you shoot a picture of me, shoot my left side. That’s my good side.” From then on, I started covering him as a senator, vice president, and president. That included covering (and following him) to Vietnam, India, and events out at the ranch. His larger-than-life presence made a huge impact on me.

at meeting to plan the 1960 presidential campaign

LAM: LBJ really made an impact on the world. As I read in your book, he seems to have made a significant impact on you and your career.

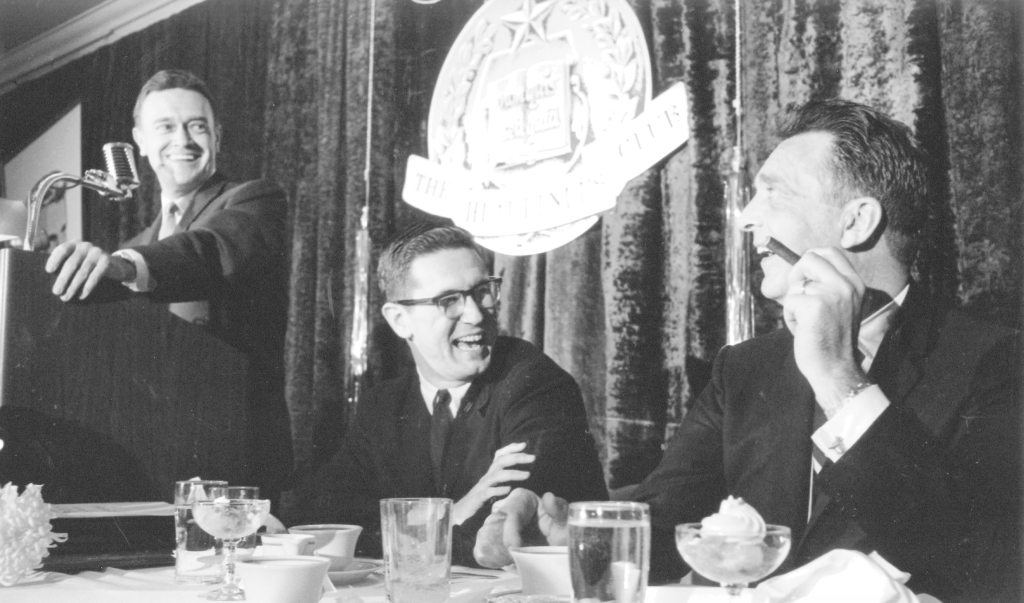

NS: I think he would have made an impact no matter who he was. Sure, he was impactful, by virtue of the offices that that he held. But then, later, LBJ had an impact on me as a person. I went to Hyannis Port, Massachusetts when he was just nominated with John F. Kennedy….I was part of the press corps there. Here I am, with John F. Kennedy and LBJ, and he says, “Neal, come on up here. You want to get your picture made?” The same photo opp happened in India when meeting with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru at the Taj Mahal. I never did follow him to the White House. But after he got back, I had my own PR agency by that time, he hired me, and as such, I was paid by The University of Texas because the school built the LBJ library. They asked me to chair the library opening event, which was a six-month job. I worked with him daily, and out at the ranch, to get the opening going. So, he was quite a presence. After a while, I wasn’t as overwhelmed by him because of the familiarity of being around him so much. He did have an impact on my life. A bunch.

LAM: You write about LBJ throughout the book, which is especially touching to me because you two are both larger-than-life personas that represent Texas. So, it was really terrific to get to know you, and LBJ, more through your writing.

NS: Oh, I will tell you that the book is not about politics, as you well know. The book is about politicians, with LBJ being the most dominant because I had the longest and closest association with him, although not on a political level. Instead, it was on a personal level and on a reporting level. So, I never got caught up in any of the politics.

LAM: It shows, as I was reading your book, what a small world this is. You had written about when you were at the ranch with the Johnson family, and touring Fredericksburg, when the German chancellors came to visit the U.S. after JFK was assassinated. My family was one of the founding families of Fredericksburg.

NS: Oh, no kidding.

LAM: It’s such a weird, small-world story. My great-grandmother passed away on Christmas Eve of 1963. You may, or may not remember this, but LBJ and the chancellors attended my great-grandmother’s funeral while they were in Texas during that time.

NS: Oh, wow.

LAM: Because my family had helped the Johnson family so much over the years, LBJ wanted to show the German chancellors, not only small-town America in Fredericksburg with its German roots but also how people would come together in the death of someone who was a German American. My much older brothers recall that LBJ, the chancellors, and the Secret Service sat in the back of the pews behind my family.

NS: Yes, that was when they went to the church. LBJ felt a kinship to the Hill Country, Fredericksburg, and your family because they were neighbors.

LAM: LBJ made a big difference to a lot of lives, and it helped spur the growth of this region then.

NS: Oh, it really did. When LBJ was working to get elected to Congress in the early stages, he worked on developing the Highland Lakes under Franklin Roosevelt by bringing electricity and flood control.

Even in his travels around the world, LBJ made those personal connections, some of which brought positive and unexpected connections back to the Hill Country. When I was with LBJ on a trip to Pakistan in 1961, he saw this camel beside the road, with its camel driver. At that point, LBJ stopped the motorcade, got out, walked over, and said, “I wanna meet him.” He walked over to him just like he might be campaigning in Caldwell county, or something like that.

LAM: Every handshake is a vote.

NS: Right. But he said to the camel driver, just in passing as he was leaving, “You come see me now.” So, the press picked it up and he invited this camel driver to the United States. Oh, my goodness. It turned it into a major publicity coup in the sense that he brought the camel driver here to the ranch in the Hill Country. For example, LBJ made a big to-do about electricity, flood control, and getting water and irrigation into this area, and helping the farmers. Then, LBJ called up his friend, Henry Ford, and said something like, “Henry, this guy’s got a camel and that camel’s gonna die someday. So can you give him a Ford pickup truck?”

LAM: Can you imagine? That’s so great. I mean that attention to the detail of every person like that. That’s the mark of a great politician for sure.

NS: It really is.

LAM: Neal, you’ve known so many fascinating people, especially from your work in public policy. Tell me about why you found it so fascinating and made a career of it.

NS: Well, you know, that’s a good question. I guess I’ve always been very, very curious and that’s a mark of a reporter. You’ve got to have curiosity so that you want to check into things and find out what’s behind what is happening. With Austin as the state capitol, you’re always surrounded by political activities like the state legislature, even on down to the city council. As a reporter, you always covered those things because they were newsworthy. So, I just literally became wrapped up in, and intrigued by, the people who were involved. Plus, you know, and there were some rascals in that group.

LAM: Right. Being curious is an asset.

NS: The key to curiosity is that you never know what opportunities it may lead to. When I went to Columbia on a CBS fellowship in news and public affairs, I went down and got credentials at the United Nations because I wanted to be a part of it and see what was going on. That was when Nikita Khrushchev was banging on the table with his shoe. And that’s when Fidel Castro came up and was a part of a General Assembly meeting. Of course, the President of the United States and all the world leaders were there. So, I got inoculated with all of this and you know, for some reason, it is just part of my DNA, I guess.

LAM: Thank goodness it has been because the stories that you reported on have made a really big difference to lots of folks. In your book, you recount with such precision, so many events in your life. Can you tell me how events can shape a journalist’s career…like it has yours?

NS: I go back to my journalism training, which frankly is different from today. You’d jump into a story, and you try to find out as much as you possibly can without bias. Then, you report it and let the people who are reading, or seeing, the story and make up their own minds. It impacted me in the sense that I was able to see just about every side of a story and that there are often more than two sides to any given story. I always had a fascination to find out about those sides. You know, I covered Barry Goldwater when he ran against LBJ. Even though I was working for the LBJ-owned TV station and was just getting to know him, people didn’t think anything about that. I didn’t think anything about that, either then. I mean, here’s a guy running for president, so I think, we’ve got to cover him.

LAM: You must be objective no matter what.

NS: Yes, exactly. And that was maintained throughout, even during the time when I was actually on the UT payroll. While I working directly, and answering directly, to LBJ on the development of his library, there was no politics involved in that.

LAM: Vietnam was such a political thorn in his side for so many years.

NS: I’m sure Vietnam was painful for him. But he didn’t dodge it. In fact, when establishing the library, we advised him, saying “You know, Mr. President, you don’t have an exhibit here on Vietnam. And he said, ‘Oh my goodness’”. And Vietnam was such a big part of his presidency. So, they changed the exhibit.

LAM: You allude to being more fascinated by politicians as individuals and public servants, more so than their political leanings.

NS: Then, politicians liked each other, or at least respected each other. Like with Ann Richards and John Connolly, both on opposite sides of the political spectrum people. I remember at John Connolly’s funeral, I walked up to Ann Richards, and she said to me, “God, I miss John. He helped me so much when I was governor.” There’s a humanness to these people who have these big titles and big responsibilities. They’re public servants and human beings. That’s what I think kept me more intrigued and interested in them as individuals, than them as a political ideology.

LAM: In your book, you talk about going fishing with George H.W. and George W Bush to profile them after W left office. Why was that important?

NS: Hey, when you sit in a bass boat with two former presidents like the Bushes, with just the three of us fishing, you get a feeling for them as individuals. Plus, I wanted to find out about the relationship of father and son who both ended up leading the free world and I got a lot of insight into them as individuals. That was my main concern.

There’s so much that is a part of people that has kept me fascinated by the political aspect of everything throughout my entire career, whether active in journalism, PR, or consulting for politicians, for instance, John McCain. I traveled with him when he was campaigning for president and worked with him on his speeches, not policy. It was just about how to deliver and communicate. We would have drinks and dinner after a long workday, or go to his hideaway in Sedona, Arizona. He would let his hair down and I asked him how in the world someone could endure five and a half years of torture in a prison of war setting like he did.

And McCain would ask me, “Neal, tell me about LBJ.” And I said, “Senator, let me ask you about Hanoi Hilton.” It was quid pro quo with giving and getting information. Sure, he talked about the torture and about how his fellow prisoners saved his life when he was at rock bottom and couldn’t even feed himself. He told me that because he had been tortured so horribly, he lost his arrogance. He began as a feisty Navy Top Gun pilot and while he was a prisoner of war, he was broken and learned how to rely on his fellow man. His fellow prisoners saved his life. They kept him alive when he was on the verge of death. That conversation was so revealing as to who McCain was as a man.

LAM: You had mentioned the phrase, and you don’t hear this very often anymore, public servant. It feels like we’re sort of operating on kind of on a different planet with all the changes going on. And certainly, in Texas, and today’s media world. What are your thoughts about that? Have we progressed, for lack of better terminology?

NS: Well, and they’ve certainly evolved.

LAM: Evolved. Yes, that’s perfect.

NS: Now when you hear me say this, remember I’m coming from being an observer, rather than someone who’s involved in it. What I’ve observed is that the world has not only changed, but the method of communication has changed so dramatically and drastically with 24 and 48-hour news cycles on your computer, TV, and phone. People tend to learn more, but I’m not sure they actually are more educated from what they are seeing. They are getting more reinforcement for whatever biases they start with.

Now, everything is compartmentalized. If you’re a Republican, you only have to appeal to basically only the Republican base these days. Same with the Democrats. LBJ had a phrase for that. He said, “What we’re striving for is the greater good for the greater numbers.” It has a nice ring to it, but it also is so important for people to sit there and realize, ‘Hey, I may not represent those views, but those people have concerns. And I’ve got to be sure I take care of those concerns as well.’ I’m not so sure today that drives public service.

LAM: I agree a hundred percent. Information doesn’t necessarily connote knowledge.

Neal, I’m so excited to be highlighting the second installment of your book excerpt next year, about the building of the LBJ Presidential Library. I think that it’s going to be really interesting, with the bark off, to learn more about it. Before we end, let me ask you about the UT Tower shooting in 1966 that was such a big part of your career. That must have been a life-changing day for you.

NS: It was. The Tower shooting was very emotional for a lot of people. For me, it’s history and cannot be ignored, even as horrible as it was, and is, to this day. I don’t mind talking about it. I feel like we need to talk about it so that we can learn from it and understand it today. You know, for instance, if that event had not occurred as it did, we wouldn’t have had EMS develop as it has today. Or SWAT teams. There was no way that any police force of any kind, anywhere, could handle that sort of event then. No one was ready for it. So, it has caused a lot of change in the world. That was the first of its kind…for a guy like Charles Whitman to climb up on top of the Tower in 1966 and indiscriminately start shooting people. No one could imagine what was happening, even though they were standing in the midst of it. To walk out on the Drag and think ‘What’s going on here’ and bang, there’s a shot and maybe they got shot themselves. In fact, when Claire Wilson, the first victim, by the way, was eight months pregnant. And then he shot her husband walking beside her and killed him. She survived, but who knows what went through Whitman’s mind.

People would just look up and stare at the Tower, still not realizing what was happening. They couldn’t comprehend the scope of it. It was a hundred-degree day. Sirens were screaming. People were shouting as gunshots were going off, both from the ground and from the up above. The sensory aspect of the whole thing is still hard to describe. It was unreal in that sense. I can still hear and see, and almost feel, what was going on that long ago. My job reporting on it was to make sense of what was happening. And I, too, didn’t know. Nobody had any perspective. If it happened today, you have a greater perspective, but at that time, it was just so horrible and out of the ordinary. And I think that’s the reason people today are still so caught up with it. But remember, that was 1966, more than a half-century ago.

LAM: Why do you believe people still remember the event so clearly?

NS: The Tower is still there. It hasn’t changed one bit, except it has some barricades up at the top that you can’t see from the ground very well so that people can’t get up there. The second reason is it occurred out in the open and our television cameras captured all of that on film. That film is still out there today. In an unexpected turn, I became the repository for all that film rather than the TV station. I felt I was given a unique responsibility to make that freely available to all. In fact, I have shared that film with all media, documentarians, and historical groups over the years who wanted to use it. With the Abraham Zapruder film of when JFK was shot, he sold that film to Life magazine and others. He made a lot of money and with this event, we gave it all away because it was history.

LAM: I’m glad you were there to lend your perspective, Neal, and lend your perspective to everything, with this new book, With The Bark Off. We are all so excited for you and are proud to call you a fellow Texan. It was an honor to speak with you.

NS: And my honor to spend this time with you, Lance. Thank you.