Houston native fashion designer, Victor Costa, is as much responsible for Texas’s pop cultural rise in the 1970s and 1980s as the T.V. series Dallas, or the big oil boom that cemented the state’s place in history. Here, in an exclusive, our fashion-savvy chronicler Geoffrey Connor, reflects on the era’s party that never seemed to end… and how Victor Costa’s designs remain timeless.

Photography courtesy of Victor Costa, archival. Additional photography by Robert Godwin

RISING HEIGHTS

In 1987, at the apex of his career, Victor Costa’s fashion line was once described by The New York Times as “flamboyant, super-feminine dresses that bare the shoulders, hug the waistline, and billow and swirl over the hips”. With good reason. The name Victor Costa has been famous in international fashion circles for over a half-century now, bringing acclaim to Texas and his hometown of Houston, in particular. He has not only created beautiful designs but also is well-regarded for his commercial acumen and marketing brilliance, combinations not always found in fashion design circles. “He’s one of the most famous names in women’s fashion,” said Houston philanthropist Joanne King Herring. “He’s made many women look fabulous over the years, and I’m so proud he’s a Houstonian.”

He’s come a long way, baby, in the vernacular of the 1970s stylish cigarette branding slogan. Costa was born in Houston’s Fifth Ward in 1935, in very modest circumstances, during the height of the Great Depression. As the middle child born to a Sicilian-born metalworker, who, with his American wife and family, lived in three rooms behind his grandparents’ grocery store. Although Houston was not exempt from the impact of a sagging global economy during that era, the city’s port and shipping channel benefitted greatly from the Texas oil boom and a corresponding growth in rubber, plastics, and chemicals. Additionally, the World War II era saw a surge in manufacturing and shipping, which added thousands of more jobs and greatly expanded the city’s economy. The Texas Medical Center was also established in the 1940s, initiating a transformation of the city’s image into a more modern, refined era.

During this time of rapid change in Houston, Costa’s family enabled him to see and experience the elegant side of the city, even if it was not their personal circumstance at the time. He has often recounted stories of shopping as a boy in downtown Houston with his mother, who had an eye for fashion, though she may not have purchased much then. It was the time of lavish department stores like Sakowitz, Battlestein’s, Foleys, and many others, that carried clothing and accessories previously available only on the east coast or in Europe. Costa was inspired by the beauty and elegance of what he saw in lavish display windows and learned to draw and recreate such style on paper dolls that he then sold to his school classmates. In high school, he even made prom dresses for his classmates.

Costa also drew upon what he saw on the big screen during the Golden Age of Hollywood. “I had access to twice-weekly tickets as a boy to see movies” said Costa. “I saw such stylish stars as Joan Crawford in some of the most spectacular clothing of the era”, he said. In fact, as destiny would have it, Crawford, for whom he would design paper doll dresses as a child, would later become a private client of Costa’s label.

As an adult, Costa’s natural talents were refined at the Pratt Institute in New York. He also trained at the prestigious Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture in Paris, whose other famous graduates include Valentino, Karl Lagerfeld, and classmate Yves Saint Laurent. Costa learned the fine art of design, and the imaginative use of fabric and decoration, while also understanding the nature of the fashion business and marketing.

COMPREHENDING COUTURE

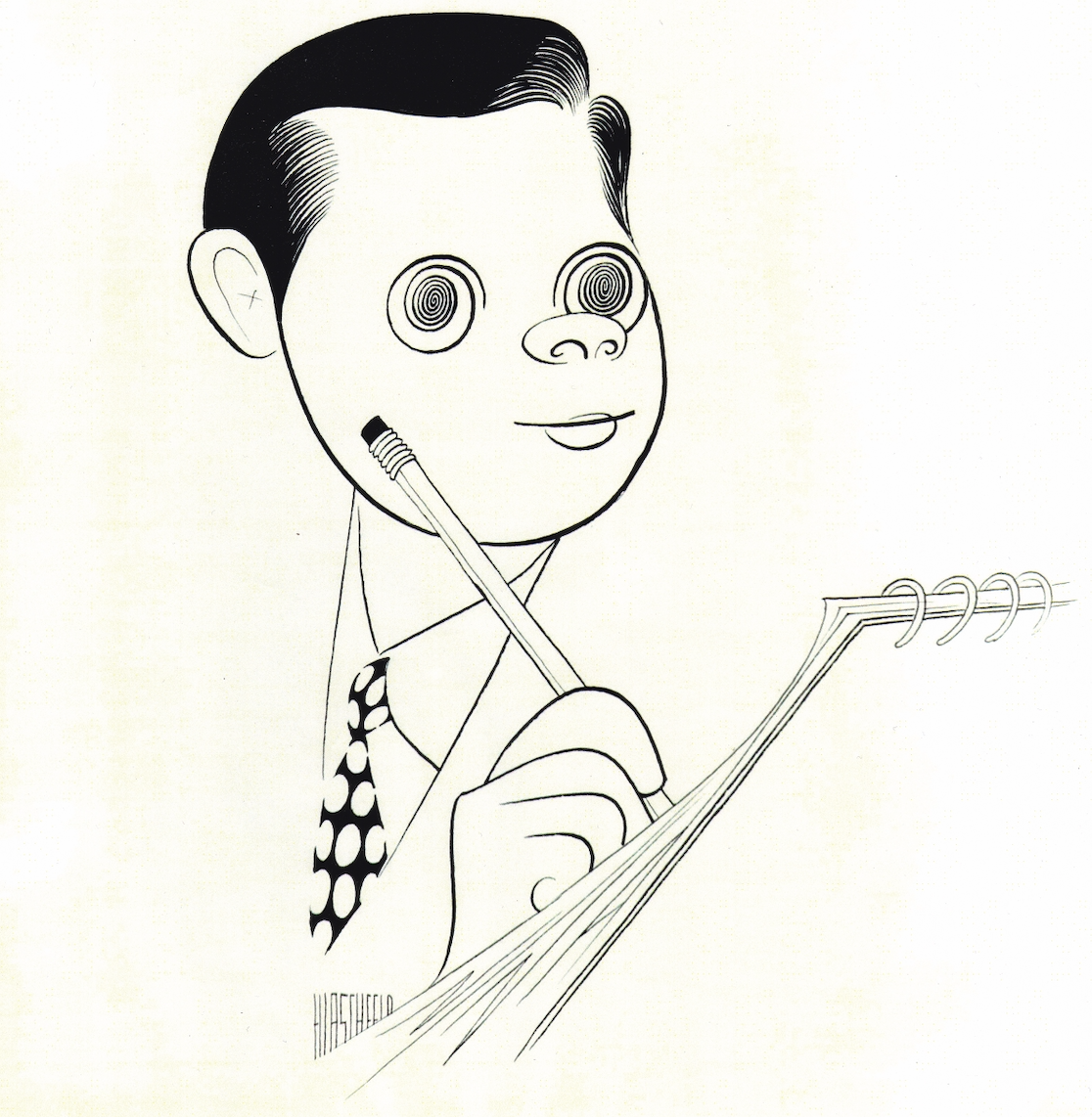

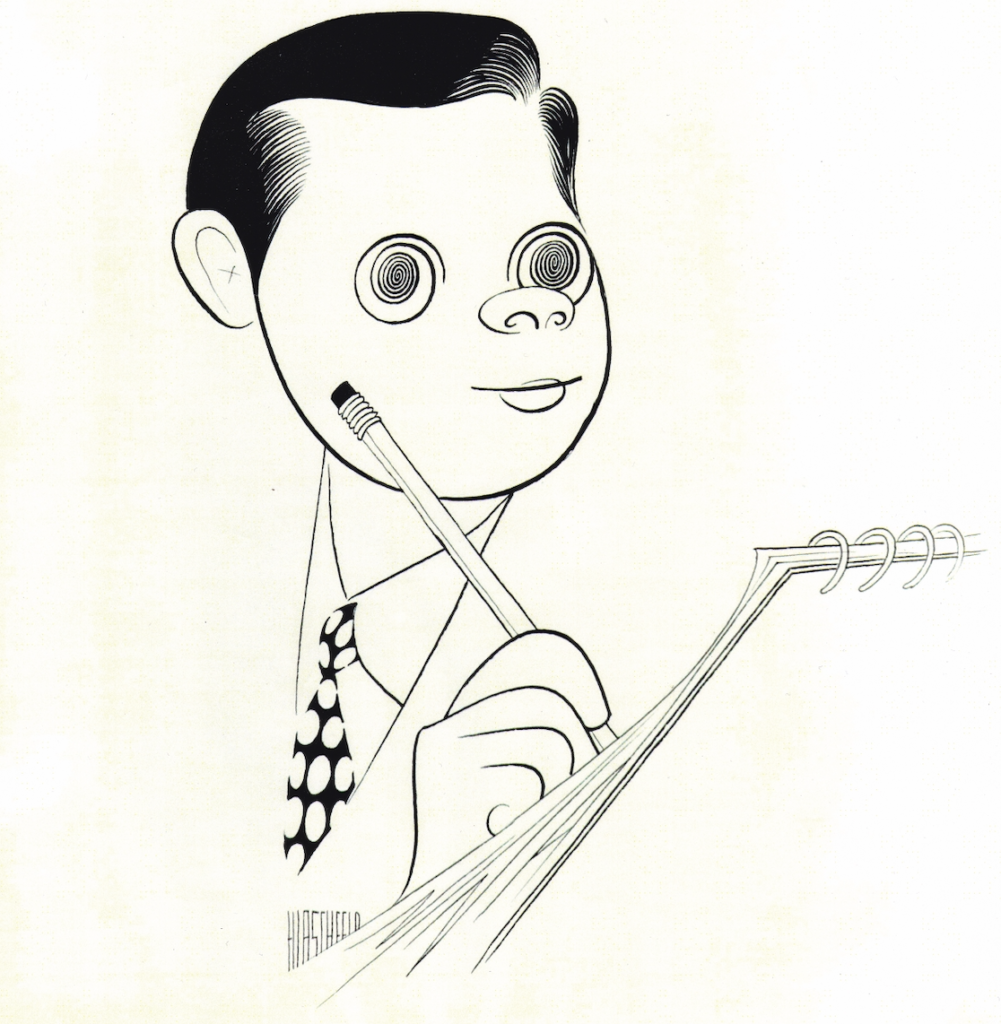

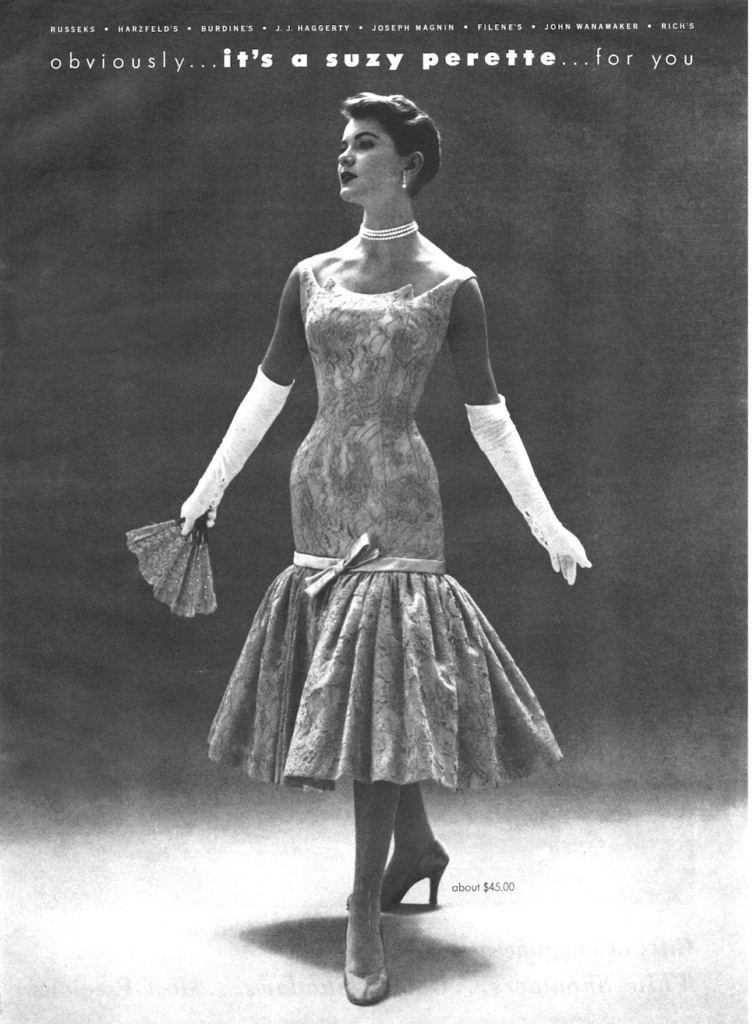

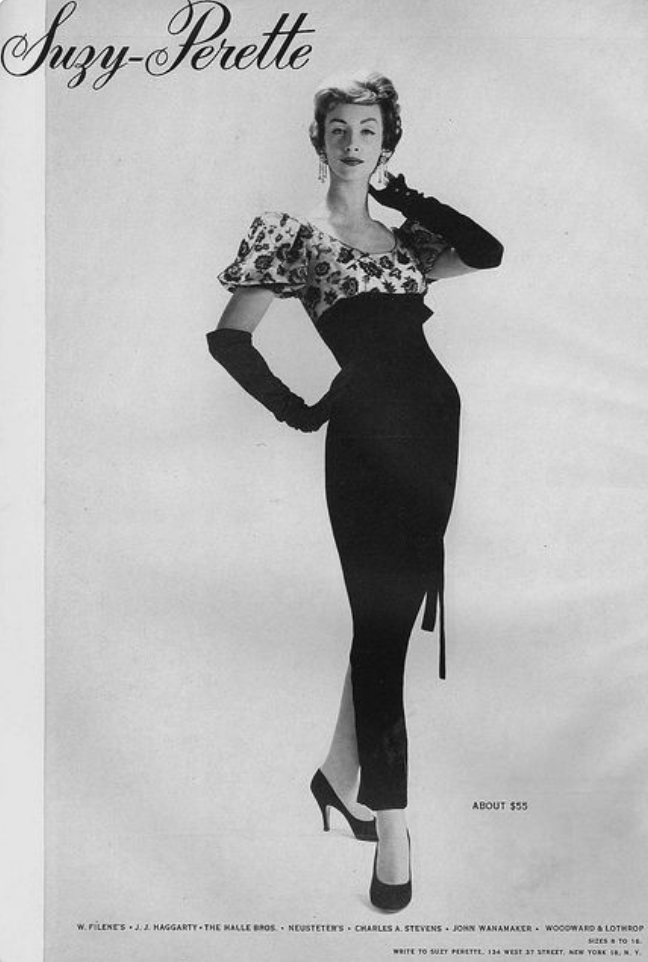

Costa then began working as a designer in New York, adapting French high fashion to the American market. According to Myra Walker, of the Texas Fashion Collection of the University of North Texas, “It helped that he had a photographic memory and a quick hand at sketching, and was able to translate what he saw on the Paris runways into successful designs for the Suzy Perette company during the 1960s. His ability to comprehend couture and ready-to-wear fashions is a complex and masterful talent. He is not content with only a quick sketch or photography, but often goes so far as to purchase the original couture design to study the construction and fabric.” It was an era of voluminous skirts, matching lining, and smart tailoring…all variables that would serve him well to design for glamour’s big comeback in the 1980s.

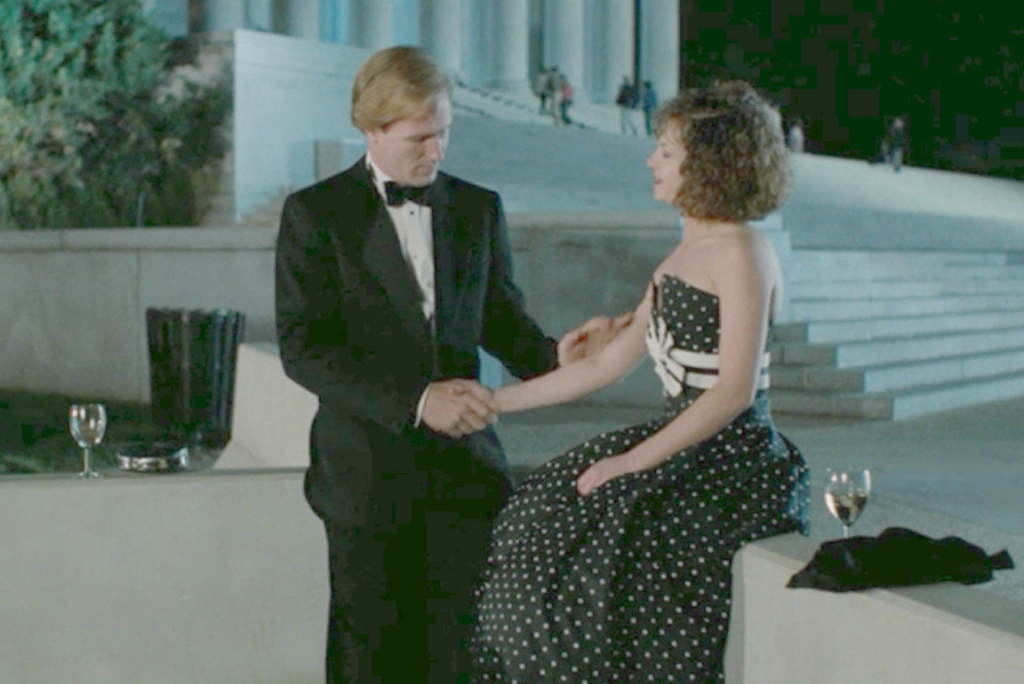

Determined to be his own designer, especially after a mentor advised him, “Don’t just promote a fashion house–promote yourself.” Costa acquired the Dallas fashion house, Ann Murray, and used his Texas operation to manufacture his designs. His clientele grew quickly to include many top buyers, including Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue and later, Nordstrom’s and Bergdorf Goodman. His extraordinarily glamorous clothing was worn by the stars of the popular 1980s television series Dynasty and Falcon Crest, and by such stars of the era as Joan Collins and Brooke Shields. By the late 1980s, his business was grossing over $50 million annually. “I adore Victor,” says Houstonian philanthropist Carolyn Farb. “He is a designer who focuses on his most important goal–to make his clients look and feel beautiful.” His presence was so ubiquitous in the 1980s pop culture that he even designed Holly Hunter’s Cinderella-esque transformation gown for the hit 1987 film, Broadcast News. Besides his commercial line, he continued designing for private clients, including Hollywood stars and American socialites who wanted their own distinct look. His appeal was as broad as the shoulders he designed because of its beauty, and deep because his clothing line was priced less than comparable designers.

Victor Costa paid particular attention to costs early in his career in order to make his fashion line available to a wide base of style-conscious consumers. Importantly, he acquired the facilities and staff needed to manufacture his own creations in-house thereby eliminating markup from a third party manufacturer. Next, he looked for ways to emulate certain design elements with a more economical approach. For example, his designs sometimes have a machine jeweled lace instead of a hand jeweled lace used by a more expensive designer, or even using an expensive trim on an inexpensive fabric to give it a glitzier look. Or, replicating a forty-dollar floral embellishment he found in Paris for just $1.50. In modern times, Costa has cultivated skilled bead workers, detailed embroiderers, and other artisans in China in order to incorporate brilliant new elements into his designs, but his bottom line was always to make beautiful clothing and, while the prices per piece are comparatively low, he sells volumes of each creation.

SOCIAL SWIRL

Although very trendsetting, Victor Costa was careful to never fall into the trap of making successful designs only for the runway or the entertainment industry. His designs were worn by women in business and society, like Estée Lauder and Betsy Bloomingdale. He helped popularize the return of the shoulder pad favored in political circles by such women as Lady Bird Johnson, Rosslyn Carter and Julie Nixon Eisenhower. “Victor has always been a gentleman and respectful of his clients,” says Farb. “He is very attuned to the place a woman holds and dresses her sumptuously, but appropriately, for her lifestyle as a business executive, political leader, social leader…or any role she has chosen.”

Costa’s skill at surveying style trends and quickly translating those into his own fashion line has sometimes provoked the criticism that he relied too much on other’s inspiration for his designs. But, of course, fashion has always been a cycle of taking another’s design and adapting and remaking it in a fresher, more practical or accessible way. Ralph Lauren famously marketed his Polo shirt for daily wear, which was much the same shirt René Lacoste originally designed for the tennis circuit decades earlier. In the same way, Costa took European haute couture and made it accessible for generations of women by using cost-effective fabrics and decoration…but with no less style and flair. The result was year after year of spectacular designs that women clamored to own. The outfits didn’t just look good on a mannequin but made the wearer look good as well.

Author Mimi Swartz once wrote that “in the right Victor Costa, a plain woman becomes a pretty woman, and a pretty woman becomes a knockout.” As Costa has said, “Special occasion dresses have always been the hallmark of my business. My quest for what is new sends me around the world. It is a sense of pride and fulfilment that some of the most noted and important women in the world are wearing my clothes. But also a young girl of 13 may get a Victor Costa dress which will have name recognition and make her feel special. Women adore how they look in their Victor Costa dresses.”

Victor Costa’s life is so easily compared to the life of his native Houston. They both started out humbly but stretched to reach around the world in spectacular fashion. Both drew on their natural resources and talents, but as they grew, they began to draw the world to themselves. Costa was always at ease in Paris and New York while being professionally successful and inspiring. Yet Costa’s roots in a city like Houston enabled him to see a market need in the fashion industry, particularly the middle-class woman with good taste and a desire to look resplendent in a crowd. Not that the wealthy elite did not also covet the Victor Costa label, but it was the mainstay consumer that really distinguished Costa in the world of international designers.

DRESS-UP MOVEMENT

While Houston has become quite the global metropolis, it has done so in a relatively short amount of time and always with the solid foundation of an industrious middle-class. The succeeding waves of Houston’s success in international shipping, oil and gas, medicine, manufacturing, technology, and space exploration have produced many millionaires and famous names. The same economic expansion has produced a huge number of middle-class buyers who want the same look and quality they see on the pages of the leading fashion magazines but at a more reasonable price and availability. For this market need, Costa has consistently delivered and with tremendous success. The New York Times reported in a 1987 profile, and Costa noted, “It’s very pleasing to me that women who can afford to buy anything feel secure in my clothes. I’m hooked on this whole crazy dress-up movement. I hope it will last, but I know the tape of fashion has speeded up. I’m going to enjoy it while it’s here.”

It’s no surprise that Victor Costa has always been well-regarded by his peers despite the occasional controversies over his designs. For years, he has been a member of the Council of Fashion Designers of America based in New York. This prestigious invitation-only organization has fewer than 500 members but includes all the biggest names of the industry including Vera Wang, Calvin Klein, Carolina Herrera, and Donna Karan. The organization is not just about prestige in an already status-conscious business, but also provides scholarships, business funding and serves as a fashion incubator program intended to help young designers launch their own businesses. Victor Costa loves the attention given to the next generation of fashion talent. Costa’s fellow native Texan, Tom Ford, is the chairman of the organization now, following a thirteen-year reign by Diane von Furstenberg. The Council has worked successfully to strengthen the influence and prosperity of American designers in the global economy, and Victor Costa has been an important part of that triumphant effort.

Now, at a spry 84, Costa has slowed only slightly. When not at his mid-town Manhattan apartment, or his home in Connecticut, he spends time in Houston, where he and his wife, Jerry Ann Woodfin-Costa, returned a few years ago to a palatial home on the twelfth tee of the Houston Country Club where they love being a part of the social community. People still talk about Jerry Ann’s triumphant chairing of the Houston Ballet gala in 1992 when she raised over a million dollars for the worthy cause, and the décor was highlighted with life-size balletic centerpieces on each table.

It’s also true that Houston and the Costas are very comfortable with each other. They are active in the Houston arts and culture scene and quite visible at society events. hey have also generously established an endowed scholarship for Retailing and Consumer Sciences students at the University of Houston.

Costa is optimistic about the future and is enthusiastic about the next generation of designers. “The key thing is to have a dream, and to know you’re going to achieve it,” he said. “When you get knocked down, you’ve got to get up again.” It’s good advice for people in general who, like Victor Costa, seek to create beauty and success in the world.