Dallas native Rena Pederson just couldn’t let the story go. As a young reporter in Dallas, she would hear about the folklore of high-dollar jewel robberies across the city in its toniest neighborhoods of the Park Cities and Preston Hollow (and even to the west in Fort Worth) in the 1950s and 1960s. The crimes, it seemed, just had to be committed by someone with access to some of the city’s wealthiest power players…the thief knew too much and always left one single clue. Was it an inside job?

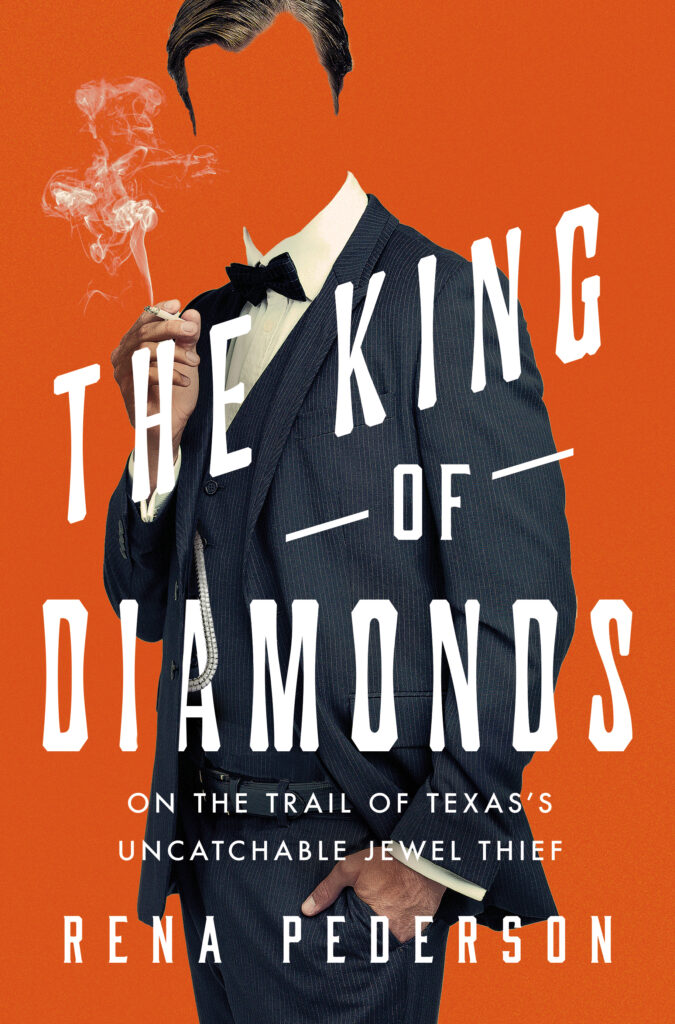

In the days well before DNA testing, the elusive cat burglar was at large and the mystery remained undetected for years. Until now, as Pederson shares an excerpt of her best-selling book, The King Of Diamonds (Pegasus Books) with our mid-century Texas devotee Lance Avery Morgan who, like you, is astonished by these plentiful crimes that went unsolved.

Excerpt from The King of Diamonds

In the swinging 1960s, a brazen jewel thief sneaked into the homes of Dallas high society – and slipped out with millions in jewels.

Like Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief, the thief pulled off his thefts with great skill. He climbed trees or crawled across rooftops to get into mansions. For more than a decade, the thief struck the affluent areas of Preston Hollow, Highland Park and University Park. He stole jewels from oil heiresses like Margaret Hunt Hill and CEOs like Jim Ling of LTV. He stole from oilman Herbert Klein, who was considered the greatest wild game hunter in the world. He took jewels from super-lawyer Glen Turner,the head of the State Bar Association, as well as W.W. Lynch, the head of the power company. His victims were the most prominent families in the city, people with names like Collins, Otis, Alexander. The press began calling him “The King of Diamonds” and everyone wondered, who was he?

Scotland Yard and Interpol were on the look-out. But the thief was never caught and the jewels never recovered. The King of Diamonds got away with the perfect crime.

A half a century later, Dallas journalist Rena Pederson has brought the search back to life.

*

The King of Diamonds disappeared like a magic trick—poof!—just as I arrived in Dallas.

It was 1970. Fresh out of grad school in New York, I was starting work at United Press International. I drove into deeply conservative Dallas with everything I owned in a red VW convertible. It had a peace symbol on the back window and Simon and Garfunkel on the radio. At the time, I had long blonde hair and a sunny sense of possibility. Real life awaited.

Because I was the newest and lowliest employee in the office, the bureau chief put me on the overnight shift from eleven o’clock at night to six in the morning, the dreaded red-eye shift. That meant that I worked all night alone in a drab basement office. The only light came from sickly fluorescent tubes that flickered on and off at random intervals—like a prison code, I thought. I was never sure if the walls were painted that sallow shade of yellow or got that way from the ever-present fug of cigarette smoke. I took up smoking in self-defense.

Although the Dallas UPI bureau served as a major news hub, it was spartan as a warehouse. The only furnishings were gray metal desks that looked like army surplus. Clunky black phones and grimy ashtrays competed for space on desks with a clutter of press releases and newspapers. Décor wasn’t important to the wire service—beating the Associated Press to news was. Reporters pounded out their stories on battered Royal typewriters, then headed for the nearest bar. I was twenty-three years old and to me, all this was glamorous.

Photo by Joseph Franzen

*

Years passed, but I never stopped wondering: What happened to the mysterious thief? There was something beguiling, almost addictive about a jewel thief who couldn’t be caught. It nagged at everyone who knew the story.

Who was he? How did he get away with the perfect crime?

A full account of his career seemed long overdue. Someone needed to reopen the case before everyone involved died.

“Why not me?” was my next thought.

After all, I was a lifelong fan of detective stories and had the bookshelves to prove it. I was drawn to the idea of solving a cold case, like coroner Kay Scarpetta, but without the scalpel.

True, nearly fifty years had passed since I first read about the jewel thief. I now had an AARP membership and Medicare card. My sporty convertible had been replaced by a sturdy Subaru. But I still had Nancy Drew’s curiosity, if not the natural blonde hair. Since 1970, I had endured five publishers, one husband, two rambunctious sons, and a lifetime of newspaper deadlines—which meant, I reasoned, that I could look for the thief with seasoned eyes.

I had seen it all as a reporter—the demagogues, the wacko birds, the kooks, crooks, and chiselers of all kinds. Or, as Zorba the Greek would say, “the full catastrophe.”

So, when it came to checking out some old jewel thefts, I thought, I can do this. No problem.

*

Right away, I learned that burglars who steal jewels have a special mystique. Even in prisons, “second-story men” are considered a cut above ordinary burglars. That’s because sneaking into bedrooms on the second floor is much riskier than a smash-and-grab on the ground floor.

Because he evaded police for so long, the King of Diamonds was a superstar in burglar ranks, the Houdini of thieves, invisible as a ghost, light-footed as Fred Astaire, and able to disappear into the night before anyone knew he was there.

Reopening the case after fifty years presented challenges. The trail was cold as a morgue for good reasons. Most of the victims and suspects were dead. And most of the records had been discarded. Though I could understand why the police might not keep burglary records for half a century, I was surprised the FBI destroyed its records after only a few years. When I asked a former agent why the files were tossed out so quickly, he suggested, “Someone powerful didn’t want them around.”

This was my first indication there was more to the story than I anticipated.

From Jack Beers. Dallas Morning News

For the next few years, I struggled to stay awake and keep the glass doors double-locked so street drunks wouldn’t stagger in. I was supposed to deal with any news that came up in the middle of the night, which was generally killings, car wrecks, and tornadoes. Like your mother says, nothing good happens after midnight, sweetheart. But while everyone else in the bureau was at home sleeping, I was more or less in charge. I liked to think of myself as the Dawn Patrol, keeping watch over the city at night.

Part of my job was keeping the teletype machines filled with paper so they could crank out news day and night. The clattering machines were my only companions and my lifeline to the rest of the world. I was supposed to monitor them and strip off the streams of paper before they curled up like pasta on the floor.

Late one night, while I was skimming through the dispatches, I noticed a story about a jewel thief who got away with millions in jewels. No one could catch him, not the police, not the FBI, nobody. The thief had outfoxed them all and had a catchy nickname: “The King of Diamonds.”

Hello there, Mr. King, I thought. You sound interesting.

And that was my introduction to the most famous jewel thief in Dallas history.

The elusive thief had sneaked recently into a mansion on Park Lane—and slipped out with $60,000 in jewels. That was ten times what I made a year at UPI. In those days, you could pay for a nice house with a yard and a garage and electric doorbell with $60,000—and still have money left over for a Cadillac. It would be equal to $400,000 today. The King had walked out with a bonanza.

The cagey thief had eluded police for more than a decade. He sometimes sneaked in while his victims were sleeping a few feet away or hosting a party downstairs. He climbed up trees and inched across rooftops. Somehow, he knew where to find the jewels.

With brazen skill, the thief had stolen jewels from oil heiress Margaret Hunt Hill, who ranked with Queen Elizabeth as one of the wealthiest women in the world . . . corporate whiz Jim Ling of LTV . . . Herman Lay of Lay’s potato chips . . . and dozens more.

For months after I arrived, there was a tremor of anticipation. Everyone thought the burglar would strike again any day. He usually did. Reporters watched and waited. I scanned the wires every night, looking for a new incident.

But the infamous thief never resurfaced. The King of Diamonds had vanished.

And all the jewels with him.

*

To learn more, I headed to a place most detectives don’t frequent—the public library. I spent hour after hour with the clip files in the Dallas Central Library, sorting gingerly through yellowed newspaper articles that flaked at the touch. By the time I left, my list of possible sources filled several pages in a legal pad.

But how would I find these people without a Ouija board? I turned to internet tools that the cops didn’t have in the fifties and sixties—Ancestry .com, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Newspapers.com.

No, I didn’t have the skills of Lisbeth Salander, the hacker in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, but I knew how to navigate public records. Sitting in front of my computer, I could find the phone numbers of people to call along with their home addresses, email addresses, family members, college degrees, divorces, arrest records, zodiac signs, and even the model of their cars and their traffic tickets. I often felt like a window peeper seeing people in their underwear, learning more about people’s lives than I really wanted to know.

I started making cold calls: “Hello, I don’t think we’ve met, but I’m doing some research on the famous jewel thief called the King of Diamonds. Yes, the one in the 1960s. Is this a good time to talk?”

Several hung up on me, but most were just as fascinated by the thief as I was. Over the next six years, I interviewed more than two hundred people—relatives of victims, neighbors, policemen, and former reporters. Each one provided information of some kind—a name, a rumor, a recollection.

The biggest surprise was the dark side of the city. Dallas is a wonderful city to live in, full of big-hearted people. I was proud to call it home. But the convivial place where I spent most of my time was the upperworld, the world of art museums, churches, concerts, shopping malls. The underworld, the domain of nightclubs, gambling dens, and sleazy cocktail lounges held more sinister secrets than I knew.

Once I started digging, I found layers of intrigue that had been hidden from view. The subsurface of Dallas harbored sex traffickers, gangsters, and even a few spies. I began to think of that alternative universe as the under-history, the part you don’t usually read about. A lot more was going on than sales at Neiman Marcus.

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 had drawn attention to the right-wing politics in Dallas, but not even the glare from that tragedy captured the full story of that time—the good, the bad, and the very reckless. As one of the detectives put it, “There were a lot of strange things going on back then.”

Getting to the rest of the story was sometimes uncomfortable. One woman threatened that if I kept asking questions, “you will be sorry.” Several people said they couldn’t talk out of fear for their lives.

This convinced me that I was onto something.

Excerpted from The King of Diamonds: The Search for the Elusive Texas Jewel Thief by Rena Pederson. Published by Pegasus Books. © Rena Pederson. Reprinted with permission.