Getting dressed up is half the fun…is the strong sentiment Texan women know better than anyone. Fortunately, there are plenty of options when it comes to getting gala-glam ready for the next soirée. Our fashion chronicler, Austinite-turned-Dallas-based Gordon Kendall, turns back the social clock to recall latter-day Texas parties when designer Mary McFadden’s talents were in full bloom. No matter the scene: the slinky 70s, the overwrought 80s, even the nifty 90s, there, amid bare midriffs, ruffles, bows, and extravagant ball gowns were always a few of them to be spotted in the crowd of revelers.

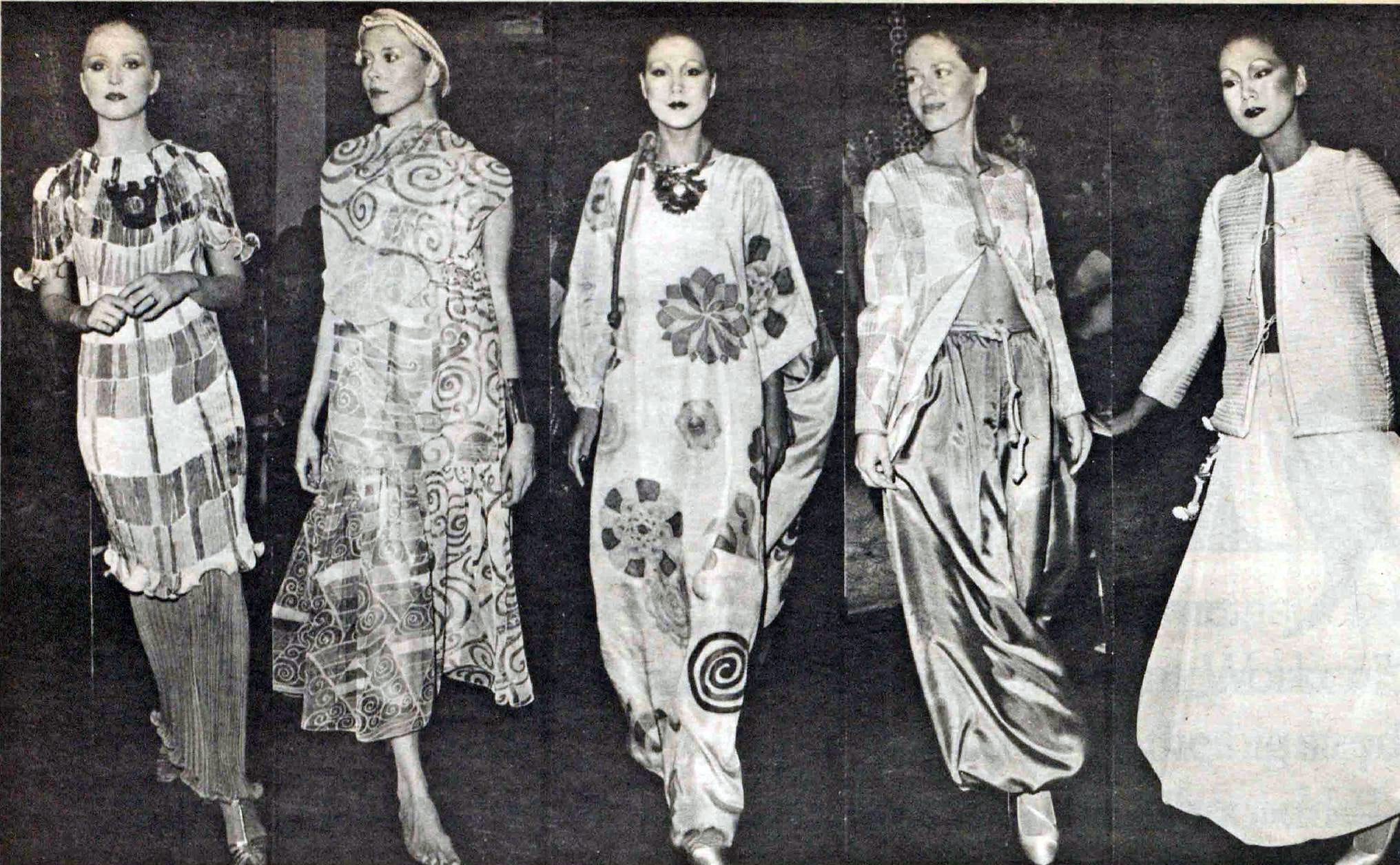

The Mary Ladies. They were in columnar gowns no matter the silhouette of the moment, sometimes unadorned, but always rife with intriguing textures, in a unique fabric, one that caught the light and shone it back brilliantly in rich colors.Other looks included sleek sheaths which featured exotic details of intricate beading, richly hued batik prints, metallic macrame, or channel stitched trapunto, featherweight silk given body. More than gowns, they were works of art in their own right. Dresses for which their “gallery” were the events in which they were worn and their frame, was the wearer. They were, moreover, pieces reminiscent of ancient Asian or African influences in their drape and layers, yet were clothing for more contemporary times. Truly, art to wear, those in-the-fashion-know, knew them at a glance. These were the creations of fashion designer, Mary McFadden.

Curated Texan has a mission to present the best of the best of McFadden’s singular designs that for over thirty years were among the very best of American fashion. No other designer did, or could do, what she did. Her death early this fall was the final coda to her business, which shuttered in 2002, yet reminds us that creativity lives on, in recollections and inspirations, of what was significant in their times and will serve as such to others. Whether her name is familiar, or not, her designs known or not, any fashion follower should take time to consider how the direction of fashion changed when along came Mary.

McFadden’s own life could rival those of the socialites and female movers and she-shakers who wore her clothing. Born to dynastic wealth going back to the nineteenth century, but not content to be only among New York’s art and cultural world, she launched her international career from a small collection first shown at Henri Bendel’s in New York in 1976…the small, chic Fifth Avenue department store was known for discovering talent. This followed stints as a fashion editor and art consultant, collector, of mostly Asian art.

Key to the Mc Fadden look was her signature and patented fabric, known as Marii. This textile began as a polyester blend woven piece good, originating first in Australia, it was meticulously dyed in Japan, and then machine-pressed and finished in the United States. McFadden’s signature textile is often compared to that made by Venetian Mariano Fortuny at the turn of the twentieth century. Fortuny designed for the artistic cognoscenti; those who understood already his arcane references to Renaissance motifs and sensibilities when they donned his clinging Delphos tunics and gowns and wrapped in his tapestry-inspired silk velvet capes. McFadden sought to educate.

She knew some women wanted their gowns to tell a story, not follow a trend. Those who relished learning as much as wearing. Fashion historians and textile conservationists can best detail the differences in time, circumstance, and technology behind his and McFadden’s fabrics. Each, in its way, is significant. Their respective rich colors and three-dimensional, vertical textures served as stage and foil for two entirely different design visions.

The University of North Texas’ Texas Fashion Collection curator, Annette Becker notes Mary McFadden’s creative eye. “She introduced many international cultural inspirations to commercially driven New York fashion. From pleating to batik and hand embroidery, she combed the world for materials that communicated histories of making to her contemporary audiences,” says Becker. Using Marii as its basis, McFadden added these elements to her designs to tell stories in each dress. From Nefertiti to Gothic, to Elizabethan, to Grecian, Chinese, and African, and with a fair number of goddesses from every spiritual realm included, each collection served as vibrant re-tellings of myth, fable, or folklore, placing her dresses in them as characters.

The Tale of Genji is but one example. In that collection, she took inspiration from the lives and stories of courtiers during Japan’s Heian period of around 1021 AD and using her palette of colors, textiles, and elements, recast their complex story into that season’s collection…intellectual…evocative….relatable. In doing so, she gave her wearers a story to tell of their connoisseurship. And a story for onlookers to admire on the gown’s owner.

Texas retailers, such as Neiman Marcus, Dallas’ Marie Levell and Loretta Blum, Houston’s Sakowitz, and San Antonio’s Frost Bros, among many others, were local homes to McFadden’s collections. Houston’s grande dame, Lynn Wyatt was famously (and often) photographed in her McFadden gowns and legions of other Texas women have their own McFadden stories to tell. “And for that, I wore my Mary…,” they note, as they recount galas chaired, weddings attended, and other social events in which they made appearances in her pleated creations. The McFadden point of view was not just aimed at the social set. Worldwide, her designs were available on a variety of licensed products. These included linens for American brand Martex, the 1980 pattern “Windrift” that was a dream-inducing print inspired by Impressionistic watercolor brush strokes, is still sought after.

Today, “brand experiences” seek to impart context, meaning, and even emotion to what can often be fairly pedestrian garments. Whatever “authenticity” they may have comes from talking points generated by design and merchandising teams. To be sure, that is the modern-day formula for fashion success, as every logo-laden garment or accessory can attest. Clothing by designers like Mary McFadden recalls a time when fashion was driven by vision. It was an era when the singular perspective of one person informed a fashion enterprise and served as an inspiration to wearers.

In the day when most American fashion businesses were fueled by the visions of men, McFadden’s point of view is all the more “authentic” and remarkable. Perhaps when subsequent fashion design students and enthusiasts see her designs, they will see more than a gown but come to understand how important it was she told the fashion story she did and how she did it in her own, singular way and her creations will likely be worn for generations to come by women who appreciate the art of storytelling.