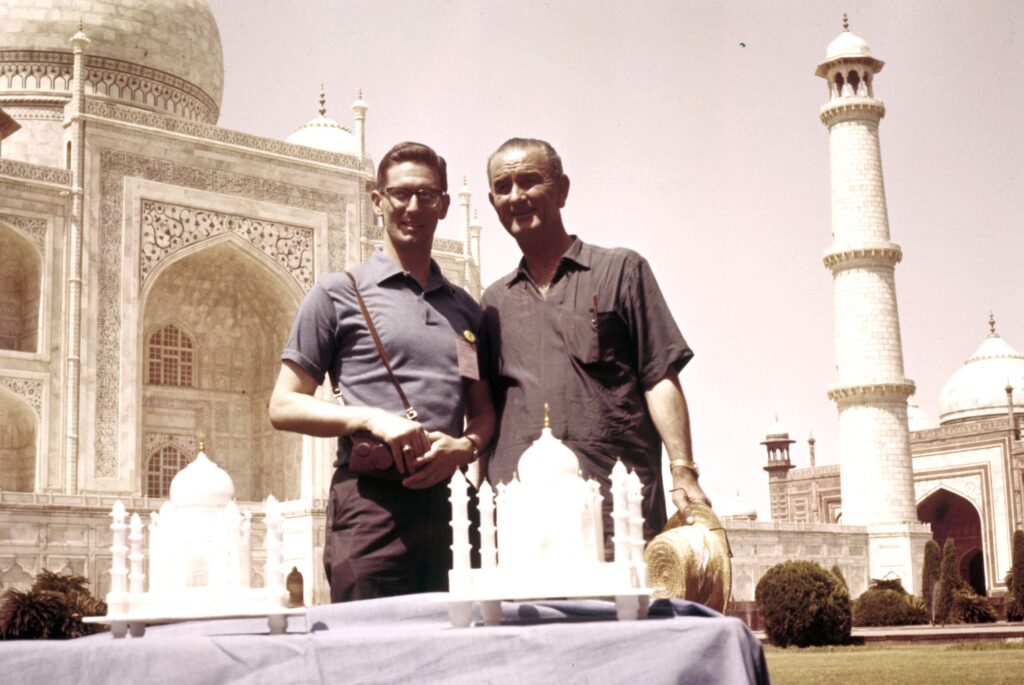

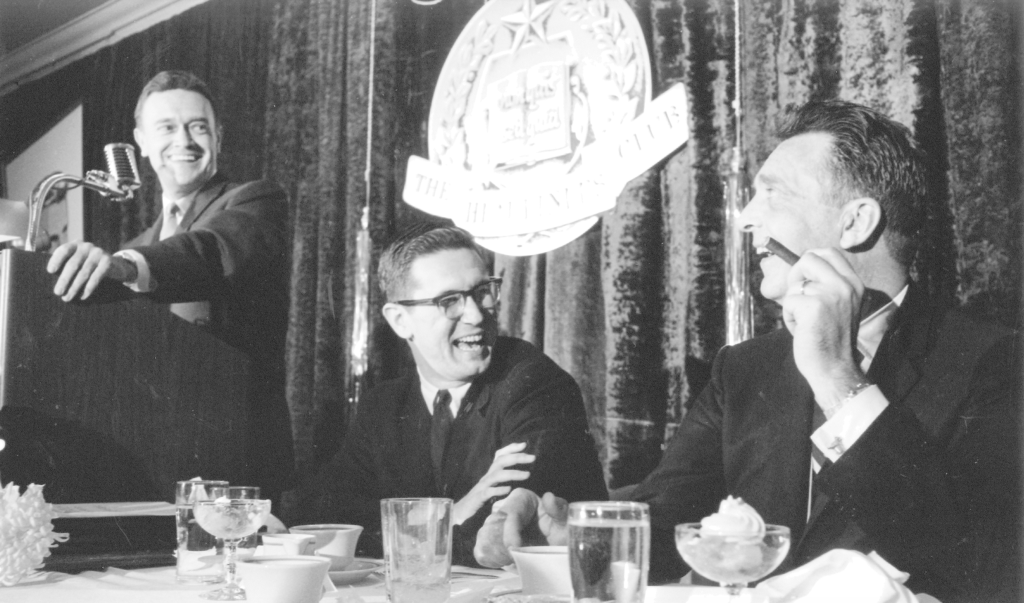

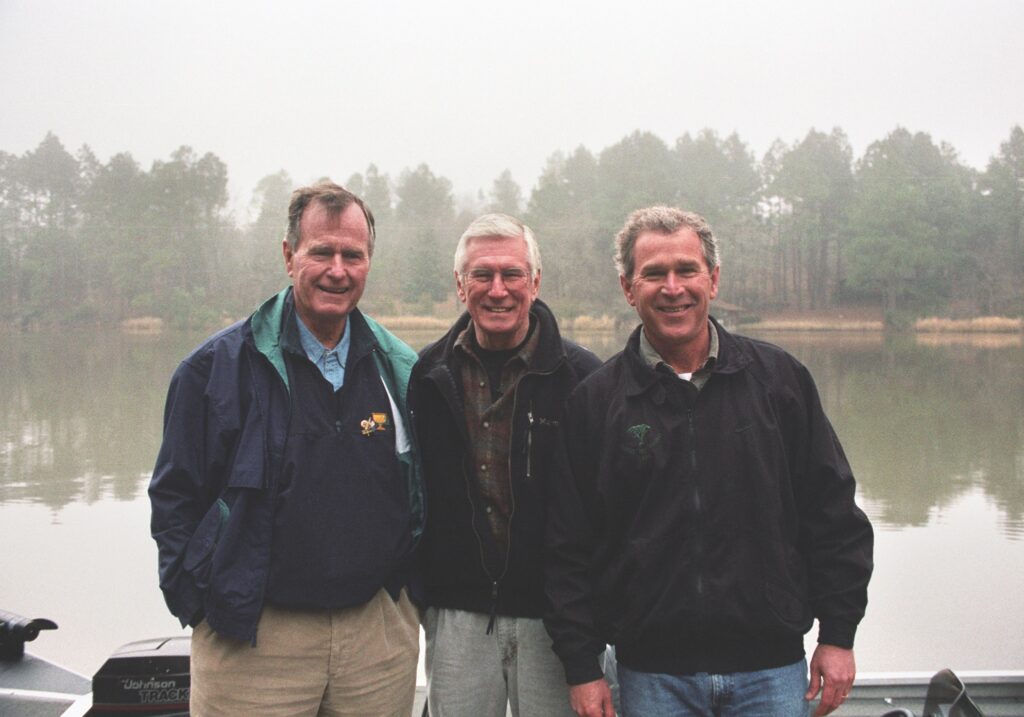

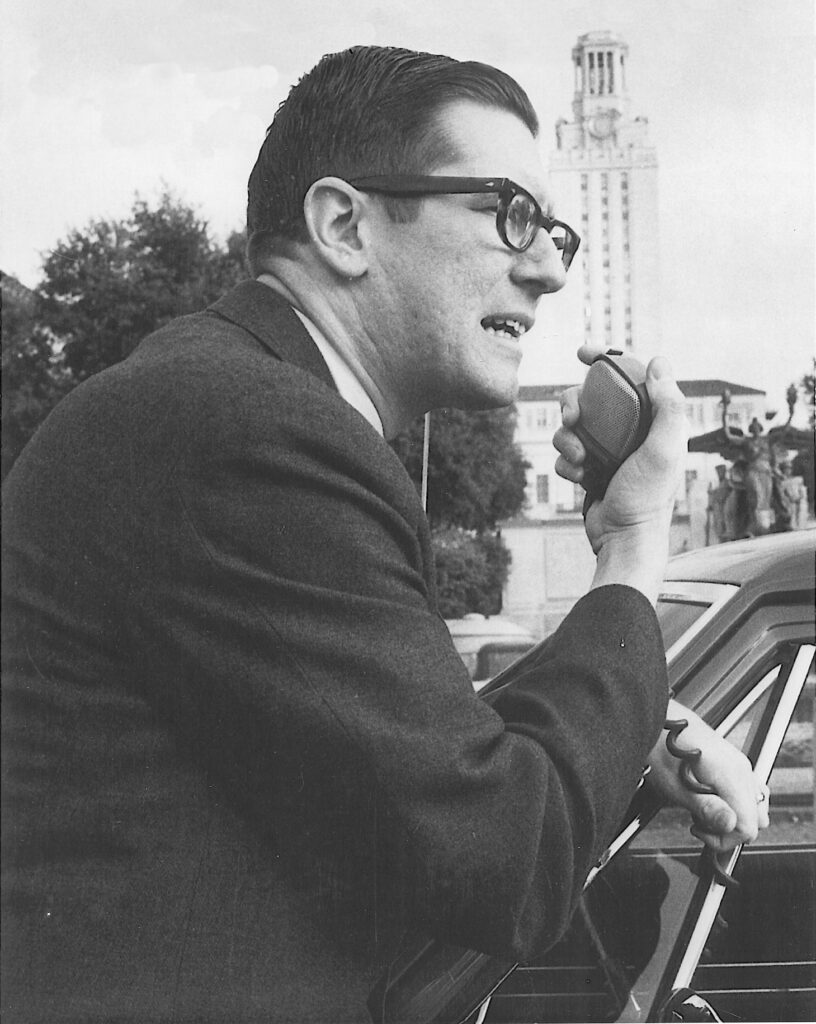

Neal Spelce is a legendary media professional and a witness to presidential history. Due to spending part of his career with President Lyndon Baines Johnson, his life course changed…as he shares in his new book, With The Bark Off, A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media. This exclusive excerpt is chock full of his recollections of the Johnson family, as well as Spelce’s point of view on today’s media landscape. Our Lance Avery Morgan also gets up close and personal with Spelce with an interview that appears here…

Photography courtesy of Neal Spelce

THE 1960 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN

When LBJ ran against John F. Kennedy for the Democratic nomination in 1960, there was an obvious contrast in age and style. JFK was youth personified—that was his image—and LBJ countered with his seasoned experience. His campaign slogan was “A Leader to Lead the Nation,” and he used that famous profile photo (the correct side) with a little gray in the temples. He worked that to his advantage, insisting that every now and then you needed someone with a touch of gray in their hair, a sign of maturity. His approach was “Kennedy is a young senator, but I’m the Senate majority leader.”

KTBC covered the 1960 primary from the Texas perspective, especially when LBJ was having a function in Austin. There was an aura about The Man. Trailing after him with cameras, we knew we were a part of history being made.

Our station was a very interested observer of the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles, when LBJ was selected as vice president. I wasn’t there; I watched it on television. We knew the players on the Texas side. His trusted aide and the future governor of Texas, John Connally, was a key supporter and a leader in LBJ’s effort for the nomination.

LBJ and JFK hadn’t been enemies, but they were combatable. (Bobby Kennedy despised LBJ until the day Bobby died.) To butcher an Ann Richards analogy, JFK was born on third base, and LBJ was born in the dugout. There was an enormous difference in their personalities, upbringing, culture, and geography. And yet they knew they had to come together to map a strategy for the Democratic campaign against Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge.

After he was selected as the VP running mate at the July convention, LBJ took the Texas Capitol press corps to the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, and I was fortunate to be invited. The White House press corps was also there covering the discussions. The two running mates considered the occasion an opportunity to get to know each other better in a casual setting and in a different light.

When I arrived, the Kennedys were throwing a football on a grassy lawn leading down to the waters of Nantucket Sound. It struck me as a summer home where everybody was on permanent vacation. The presidential candidate and the vice presidential candidate were wandering around the lawn, and the press was observing their every move.

The public scrutiny didn’t seem to bother the Kennedys. They didn’t appear to be posturing; they were being themselves, wearing sneakers, khakis, and open-neck shirts. Their press conferences were informal, un- like those in previous administrations and today, where everything is well scripted. When JFK approached the press corps to make a statement, he didn’t wear a tie or a jacket, per tradition, usually just a golf shirt. He was open and direct about their plans: “Lyndon is going to work the South, and here are a few other things we’ve decided on.”

On one occasion, Jackie Kennedy very graciously came outside to say hello to the press. What a beautiful lady! She was pregnant with John Jr. at the time, and she was positively glowing. Like everyone else in the country, I was impressed with her. She wasn’t trying to make headlines; she was simply an elegant and charming hostess greeting her guests. She understood the importance of good relations with the media.

There was a special moment for me when I was standing with both JFK and LBJ on the porch at the compound, and LBJ asked, “Neal, you want to get a picture with us?”

“Well, sure.”

Vern Sanford, who was the Texas Press Association’s executive director, was there with his camera. “Vern, come over here and take a picture,” LBJ said.

Sixty years later, it’s hard to believe, but I actually appeared in a photograph with LBJ and JFK. It’s an absolute treasure—the young Neal Spelce standing between two monumental figures in twentieth-century American history who would eventually serve as presidents of the United States. And there I am, shaking Jack Kennedy’s hand and looking into the eyes of Lyndon Johnson.

Back at KTBC, everyone saw the photo and a joke went around the station: “Neal, you certainly know who your boss is, don’t you?”

LBJ ASCENDING, 1961–1963

Once LBJ became vice president, his Secret Service detail was in and out of the KTBC building in Austin all the time. We had some fun with them. I owned one of those retractable pointers that professors use, and I would get on the elevator with the agent assigned to elevator duty and pull out the retractable pointer like a walkie-talkie and speak into it—“Secret Service on the elevator, stand by”—and collapse the pointer and put it away. Their heads would jerk around. When I went into the lobby: “In lobby now. Secret Service clearly visible.” I would do that every time there was a new agent, and I was lucky they didn’t throw me to the floor.

I had been to the LBJ Ranch for small events before he became vice president, but it was when he served as VP that the ranch became a folksy, comfortable gathering place for world leaders and a familiar geographical reference in the public mind, like Hyannis Port and Warm Springs, Georgia. And of course, when he was president, the ranch became known as the Little White House.

LBJ loved hamburgers made at the Night Hawk, a beloved institution among Austin’s most popular restaurants. The original place was located at the south end of the Congress Avenue Bridge and had been in business since 1932. Harry Akin was the owner and later elected as mayor of Austin, and he was an early supporter of LBJ. Every time the Johnsons hired a new cook, LBJ would phone Harry Akin and tell him, “Harry, I have someone I want to send down there. I want you to teach him how to make those burgers like you make them.”

LBJ’s favorite was the Frisco Burger, with its Thousand Island–like special sauce on a buttered and toasted bun. After the cook was trained, LBJ would sit in his suite above the KTBC studio and eat Frisco Burgers the way they made them at the Night Hawk.

Harry confided to me that LBJ was the one who told him to integrate the Night Hawk. He said, “You’ve got to lead on this, Harry. We’ve got to serve Negroes.”

Harry had already been hiring minorities to work in his kitchen and as wait staff for many years, but serving African American diners was a bolder step during those volatile times. When he decided to integrate his restaurants, there was no muss, no fuss. He just did it. I don’t remember anyone making a peep.

During that same period, in the spring of 1960, African American students from UT and the historically black Huston-Tillotson College had begun to conduct sit-ins at the lunch counters downtown on Congress Avenue at Woolworth’s, the Kress five-and-dime store, and other variety stores and department stores. In Austin, there were demonstrations on both sides of the integration issue, but by May of that year, thirty-two lunch counters and restaurants in Austin had voluntarily desegregated. It was a relatively quick and peaceful transition.

LBJ really did surprise people. As a southerner, he was able to push for social progress and accomplish many things that were not expected of him. Observers assumed that a northeastern liberal like JFK would lead the charge on progressive social issues, but it took a liberal southern Democrat to get things done. He achieved significant success because he’d come up through the Senate and knew how to twist arms. Literally! I’d seen him do it. He would lean over you with that large physical frame and tell you exactly what you needed to do or say.

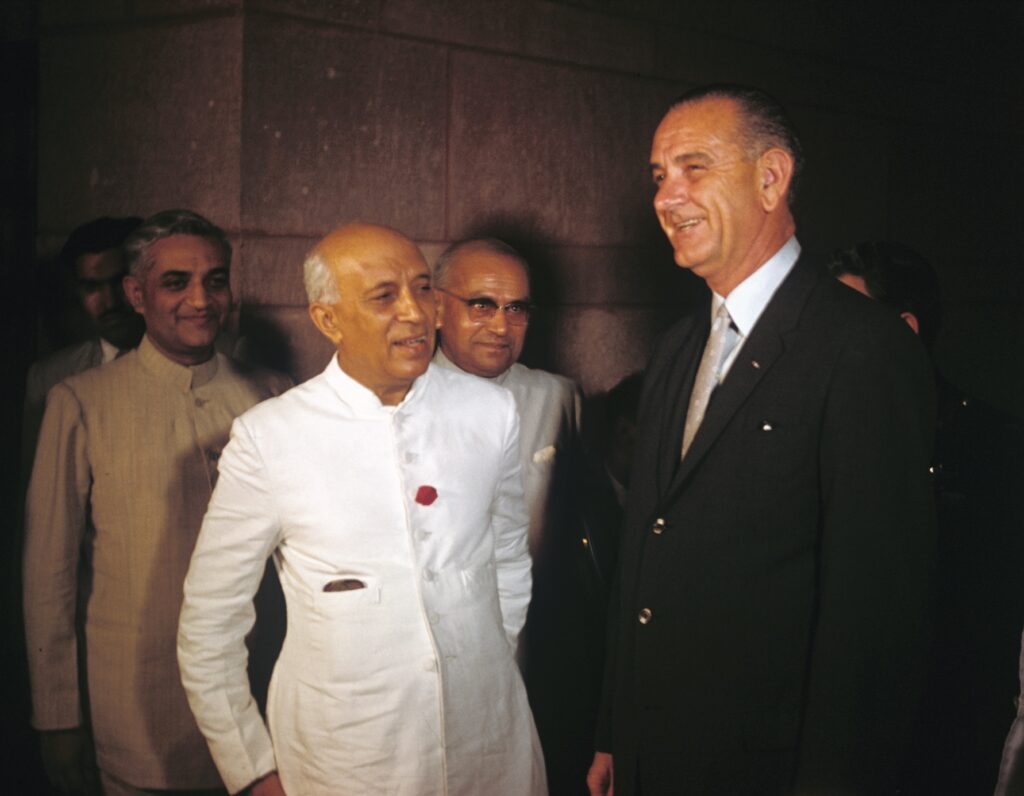

With Lyndon Johnson serving as vice president and later as president, Austin was becoming more visible in the national consciousness. When- ever world leaders arrived, they’d have to land at Bergstrom Air Force Base (now Austin-Bergstrom International Airport) outside Austin and then be driven or choppered out to the ranch in Stonewall, Texas, which is sixty miles away. The ranch had a small runway that could handle two- engine planes, but not the larger ones. Whenever LBJ or someone else was due to land, the Secret Service would rush out to the landing strip and chase the deer away so there would be no mishap while the plane was touching down.

In time, Austin became an extension of the ranch itself, not only be- cause of the proximity, but also because the White House press corps would stay in Austin when there was a newsworthy event at the ranch. They usually stayed in the Driskill Hotel downtown, and besides their coverage of LBJ, they soon they began writing sidebars about the charming college town.

Previous presidents didn’t have a colorful ranch. LBJ owned cattle and horses and an expanse of land along the Pedernales River. (The proper Texas pronunciation of that river is PURR-de-NAH-liss.) He provided deer hunting and exotic game. By Texas standards it was little more than a gentleman’s ranch, but he had a ranch foreman to make it official—and the barbecue was fantastic.

LBJ had great fun with his visitors. He enjoyed entertaining them. I could see him get a twinkle in his eye whenever he was about to pull a prank on the tinhorns. He loved to drive around his ranch and check on his cattle, and on a few occasions I went along for the ride. He owned a small German-made Amphicar convertible, lagoon blue in color, that could float and maneuver on water. But he didn’t tell his guests it was an amphibious vehicle. They’d get in the car and he’d say, “Let’s go look at the ranch. I’ll show you my cattle. I’ve got this bull out here you gotta see.”

The Pedernales River flows through the ranch property and runs over a little dam, and although passengers can’t see this from a car, the water is streaming over the top of a road. LBJ would drive along, talking about his property and pointing out its woodsy features to the visitors, and then he’d suddenly head straight into the moving water. They didn’t know he was driving on a little strip of road. At other times, he’d shout that the brakes had failed and he’d steer the car splashing into a small lake. While the terrified passengers were catching their breath, he would laugh and guide the amphibious car toward dry land.

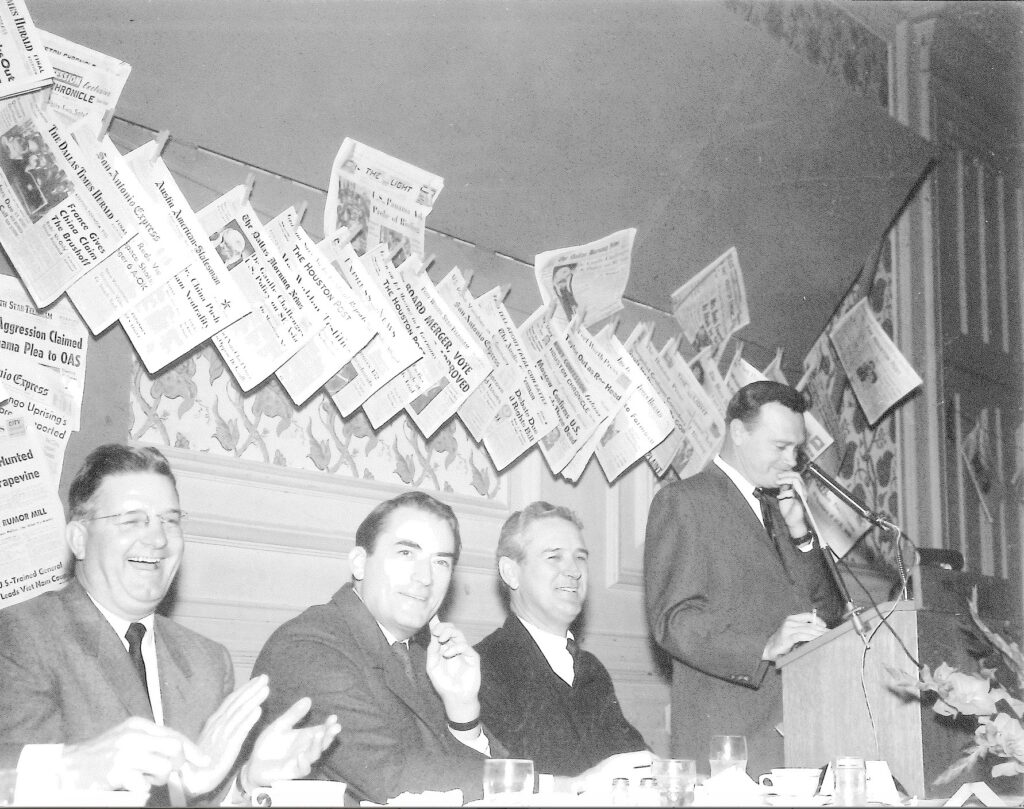

BOTH SIDES JOURNALISM

When Barry Goldwater was running against LBJ in 1964, the Republican presidential nominee booked a campaign stop in Austin, in the heart of LBJ country. Goldwater was a pilot, and he flew his own plane, a fairly large DC-3. We reporters headed out to the old Mueller airport in East Austin, and when Goldwater rolled to a stop on the landing strip, we were out there with our cameras. His sup- porters were there, too. He pushed open the pilot window and stuck his head out and waved to the crowd. “I’m glad to be here,” he said. “When I took off from Phoenix, they asked me if I’d ever been to Austin and if I knew where it was. I said, ‘No, I’ve never been to Austin, but I’m gonna fly east and when I get to a fairly good-sized city with only one TV tower, I’m going to land.’”

Folks were amazed that I put that on the air because it was “critical of LBJ’s family ownership of the KTBC-TV station.” But I said, “It was a great quote.”

In all the years I was working at KTBC as a reporter and then as news director—making decisions about what stories to air and what not to air—never once did LBJ or the Johnson family give orders to cover this and not that. There were newsworthy events at the LBJ Ranch, and we’d go out there with reporters from all over the nation to cover a prime minister or some other visiting dignitary. That was news. But we were never told “you must come.”

In one case, Walter Jenkins, one of LBJ’s trusted aides, was arrested for a sexual liaison in a men’s room in Washington, DC, and it was a serious scandal. Mrs. Johnson was very supportive of Jenkins, but in spite of her objection, President Johnson accepted the aide’s resignation.

I ran with the Jenkins story on the air, and the next day I received a call from Time magazine. “Spelce, we’re just checking around the coun- try to find out how this Walter Jenkins story was covered. How did you cover it in Austin?”

“We led with it at ten o’clock last night.” The caller said, “You did?”

“It was the top news story of the day,” I said, “so we led with it.”

They were trying to find out if KTBC had buried the story because it was negative toward LBJ and his family. Our coverage was indicative of how we handled the news at KTBC, even when it wasn’t advantageous to our owner.

That objectivity had been instilled in me by the University of Texas School of Journalism and by Paul Bolton. He was a stickler for getting a story accurate before putting it on the air. Get it first, if at all possible, but get it right, and let people draw their own conclusions based upon what you report. Don’t hide it, don’t dodge it. If it’s out there, it’s out there, and it’s your job as a reporter—as someone who’s conveying important information—to present the facts. The topic doesn’t matter. You want the viewers to say, “Wow, I didn’t know about that.”

Today, there are so many ways for individuals to get news. With the Internet and twenty-four-hour cable news, viewers can go anywhere and find whatever they want to find, with whatever stripe they may want to put on it. But back in the 1950s and 1960s, KTBC was the sole source for television news in Austin and we had a serious obligation to cover it accurately and make sure the facts were correct. I always tell folks, “Don’t rely on a single source. Whenever you’re looking for news, broaden your scope. If you want to watch a left-leaning channel, watch a right-leaning channel as well, so you can balance your judgments and make up your own mind.”

In today’s world, that attitude is considered quaint and out of step with current realities. Sometimes I sound like a Pollyanna, even to myself, but that’s the way I roll.

In my view, polarization is a problem in our society. Most people watch or read to reinforce their own worldviews. And although they’re passionately engaged, they’re missing something if they don’t explore various websites and check other programs and read this blog or that article. I love to go to the online aggregator sites that represent different viewpoints and report on a variety of subjects. I encourage people to get a more complete picture, so whatever their position may be, it’s either reinforced or questioned. It’s important to challenge our assumptions and biases.

Now in my seventh decade as a reporter, I’m often asked, “What do you think about that story that broke today, Neal?” I usually respond, “I was fascinated by it.” Not believing the story, necessarily, but fascinated by the news itself. After so many years in the business, I’ve found a way of standing back and looking at things philosophically.

I’m intrigued by what the left does and what the right does and how everybody reacts to that. I don’t get caught up in “I’m taking his side, and the other side be damned.” I think it goes back to that journalistic train- ing. You’re trained to walk into a situation, whatever it may be—a city council meeting, a public hearing on rising water bills, a school shooting—and analyze what’s going on, what’s newsworthy, what’s most im- portant to your audience. And then you write the story. You don’t get caught up in “Don’t quote this person, but quote this person.” The pursuit of balance and objectivity has carried me forward throughout my long career.

News analysts are everywhere now, but they’re not really that new. I can remember back in the early days when Eric Sevareid would come on CBS as an analyst and commentator. Dan Rather told me one time, “I envision what happens in Eric Sevareid’s life. I can see him waking up, putting on his robe, padding to the front door in his slippers, and picking up several newspapers and reading through them. And then he gets on the phone and says, ‘I think I’ll talk about this today,’ and calls that person and they go have lunch, usually with a martini. And then Eric comes to the office and sits down and writes his piece and records it and goes home. What a life!”

Dan was out there getting punched in the gut, stalked, and shot at, but there’s Sevareid having a martini at lunch.

To be fair to Eric Sevareid, he’d covered the fall of Paris to the Germans in World War II and later parachuted into Burma from a crashing airplane, so he deserved those martinis, because he’d earned his status as a commentator. I watched his analysis over the years, and I’m not sure he ever took a hard right or hard left position. He’d say, “Here is this and here is this, too, and there’s going to be a big battle over this, and we’ll have to watch and wait and see.”

A turning point in polarization may have come with the popular “Point-Counterpoint” segment of 60 Minutes, which aired from 1975 to 1979, a weekly debate between liberal Shana Alexander and conservative James J. Kilpatrick. It was famously satirized on Saturday Night Live, with comedian Dan Aykroyd (Kilpatrick) often replying to Jane Curtin (Alexander), “Jane, you ignorant slut.” I’m not sure if it was the humorous satire or the “Point-Counterpoint” segment itself, but that formula exploded all over country, a harbinger of the future.

Today there are entire teams of folks out there analyzing, pontificating, and arguing “I’m right, you’re wrong.” It’s sometimes entertaining, but usually produces more heat than light.

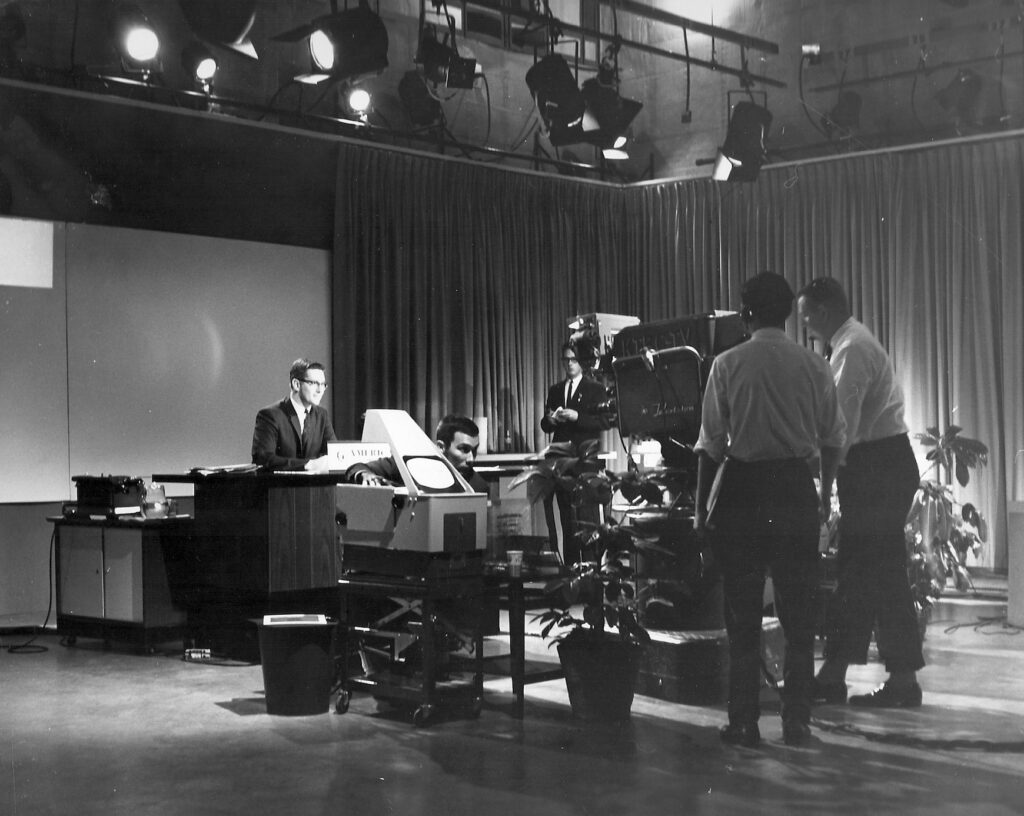

After I left daily television, I was often brought back to analyze the voter returns during election night coverage. One evening during a state- wide race, I was sitting on the set with the anchor and co-anchor, and I had my yellow pad and pencil in front of me. As election returns came in, it was my job to announce that at 7:00 p.m., this candidate was ahead, and at 8:00 p.m., South Texas had not been counted yet and voting in Houston was heavy. That kind of thing. It’s what computers do now, but all I had was a yellow pad and a number two pencil.

The anchor sitting next to me wasn’t the brightest bulb on the porch, and when I said, “We’d better keep an eye on this. The margin is narrowing, and it looks like the other candidate may win,” he said, “Really, Neal? He’s been behind all night long. How can you say something like that?” And I very calmly and quietly said, “Because of the trendline and votes that are still uncounted. South Texas is normally going to go in this direction, and they’re not in yet—and that could put this candidate over the top.”

That’s the kind of pad-and-pencil analysis I did back in the day, and that’s the way I like to watch election returns now. But the computers are so far ahead of everybody, they calculate results down to the minute and report, “We can now declare a winner in the congressional district northeast of Dallas.” Not to mention, “Hey, California and the West Coast, the election is already over and we’ve declared a winner. Your vote is superfluous.”

The Donald Trump election of 2016 is a great example of how analysis can go awry. All the ratings and data showed that Hillary Clinton was going to win. I’d been watching a lot of television coverage, and I stayed up to speed on what was happening. Two or three days before the election, I made the comment, “Trump can win this.” I mentioned that to a pollster who was polling for Trump and the Republicans, and he said, “There’s just no way.” But I insisted, “I don’t think the polls are right.”

I’m not claiming credit for predicting Trump’s victory, but when I was seeing such large, passionate crowds at his rallies, I tried to figure both sides journalism out, “Who the heck are these folks who are so angry and engaged?” And I realized that those folks were not being polled because they were “anti- media” and “anti-polling”—“I’m not going to talk.” Nobody looked at their numbers. But sitting back in my armchair and watching news coverage week after week, I could see what was taking shape. So when I made that “bold prediction,” I was dismissed, but it came to pass.

It’s the job of the reporter to analyze what’s happening with a cold eye to the truth. Polling has become essential, for better or worse, to that highly competitive media world that has emerged over the past thirty years. Unfortunately, the polls sometimes drive public opinion instead of the other way around. I have examined polls, and even conducted polls when I ran my PR firm, and I know that you can direct the results by how you phrase the questions.

When John Connally was running for governor of Texas for the first time in 1962, he was not well known and he was running against a sit- ting governor, Price Daniel, who was pretty doggone popular. One of Connally’s tactics was to encourage his supporters to vote early. It was a unique idea at that time, and reminiscent of what candidates do today. His campaign would contact the Austin American-Statesman and other newspapers and say, “I understand there are big crowds at the polling places right now, voting early. You ought to send a reporter out there and find out what’s going on.”

Of course, it was a set-up. The reporters would ask the early voters, “Who are you voting for?” and the response was usually, “I’m voting for John Connally.”

Governor Price Daniel’s response was, “My voters can go vote tomorrow.”

But the overall effect was it looked like an enthusiastic groundswell for this unknown candidate named John Connally. The press was being manipulated by his campaign. It wasn’t the first time that a political campaign had outmaneuvered an opponent, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Spelce’s memoir, With The Bark Off, A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media, is published by the University of Texas Briscoe Center for American History. Itis available in hardcover, e-book, or audiobook on Amazon.com, or wherever fine books are sold. For more info, or for a personally signed, first edition copy of the hardcover version, visit NealSpelce.com.